BAS editor Stephen Hart1

The scene is Hunan Normal University in China, and I am teaching a course that involves translating Latin American poetry into Chinese. Not a topic that I would have foreseen leading us back time and again to East-West relations, and yet it does…. How so?

Our classroom discussions often focus on nitty-gritty issues such as the poets’ biographies, the historical and political context, and the difficulties involved in translating certain words from a European language into Chinese. Broader issues also arise that, for want of a better term, I describe as cultural diplomacy. These include questions such as: how do we capture the difference in terms of individual sensibility when translating from a Western to an Eastern context, and vice versa?

One of the poets I chose for the translation task was the Peruvian César Vallejo. His work seems well suited to the task because of its high quality, semantic difficulty and the paucity of translations of his poems into Chinese.2 Of the 19 students in the Español Avanzado class, five chose the assignment of producing new translations of two of Vallejo’s poems from Poemas humanos, writing an introduction to Vallejo in Chinese for the general reader, as well as a commentary on the poems.

The translations were discussed individually and in group format. The preliminary discussions covered themes such as how to negotiate the relevant translations and scholarship on the poems, and how to achieve the right balance between translational accuracy and idiomatic naturalness in the target language..

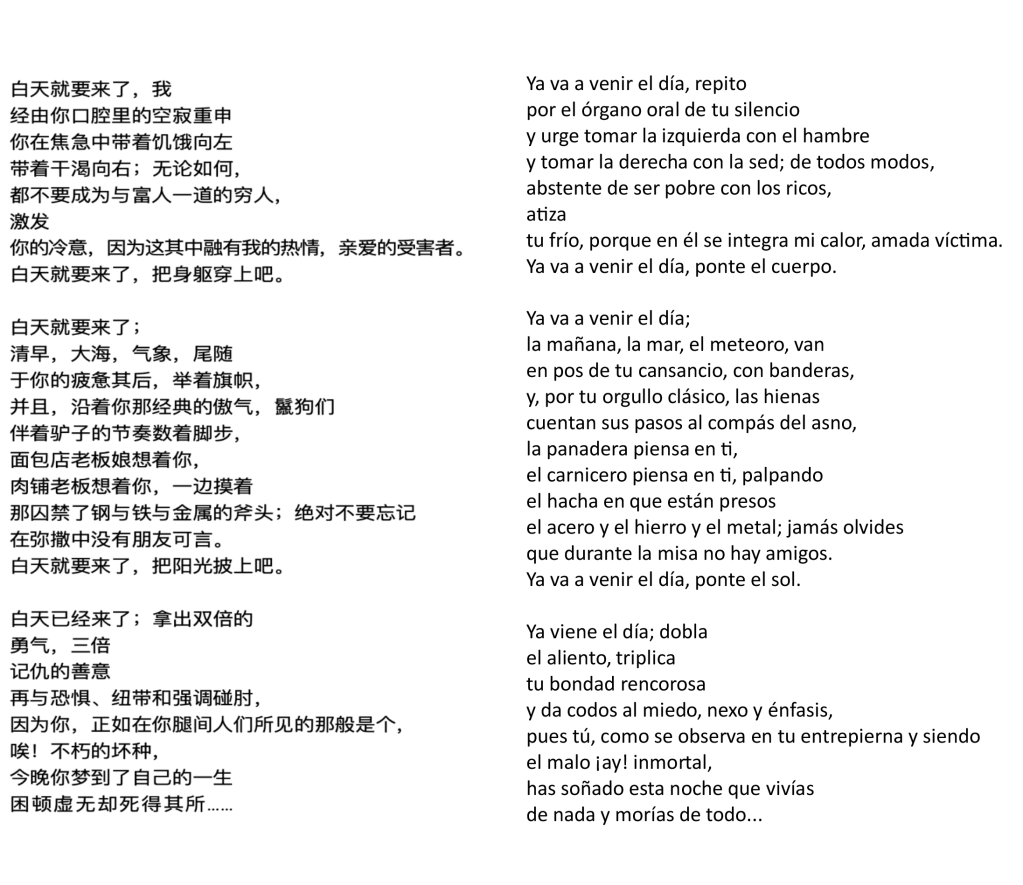

Here is an example of one of Vallejo’s poems, “The Wretched”, translated into Chinese by 卢卡 (Zhu Xianqian):

We discussed linguistic as well as cultural concepts as they circulate through the poem. We dealt with the Peruvianisms first of all, the fact that “saco” means “jacket” rather than “sack”, and “pararse” means “to stand up” rather than “stop”. We noted that the second stanza refers to Peruvian folklore, and how it is seen as a sign of bad luck if you lose a tooth. And we thought it would be advisable to spell out that in lines 4-5 of the fourth stanza Vallejo is alluding to the dialectical struggle between the “nation/nationalism” favoured by the West and the “state/communism” favoured by the Soviet Union (as it was back then in the 1930s when the poem was written).

We also felt that, in the sixth stanza, it would be preferable to draw attention, perhaps in the form of a footnote, to the Christian leitmotif of Christ described as bread/body and wine/blood in Holy Communion, as well as the trinitarian associations of “miedo, nexo y énfasis” in the sixth and final stanza. Zhu Xianqian, the translator, decided to use some linguistic devices and techniques from ancient Chinese poetry – in which words are deliberately used in such a way as to have multiple meanings – in the translation in order to echo the multiple meanings and associations evoked by Vallejo’s poem. The general assessment was that, despite the superficial alienness for a Chinese reader of some of the leitmotifs in the poem – such as, in particular, the description of the Christian rite of Holy Communion which is, furthermore, treated in a creative manner as if the baker and the butcher were really about to kill their victim during the Mass – other rhetorical ways of bridging the gap were found.

We also bore in mind the historicity of the translation-act – i.e. what does it mean to translate these poems at this historical juncture? – and there was some related discussion of the growing rapprochement between China and Latin America that has been gaining pace since the second decade of the twenty-first century. In a thoughtful article published in 2018, “The Rise and Fall of Soft Power”, Eric Li argued that soft power, a term first used in 1990,3 was running out of steam, and that the only country that was still taking it seriously was China:

It [China] integrated itself into the post-World War II international order by expanding deep and broad cultural and economic ties with virtually all countries in the world. It is now the largest trading nation in the world and in history. But it steadfastly refused to become a customer of Western soft power. It engineered its own highly complex transition from a centrally planned economy to a market economy, yet it refused to allow the market to rise above the state.4

Rather paradoxically, this did not mean that China does not believe in soft power; rather it created its own version that diverged from the western mould, as Eric Li argues:

China is now refocusing from hard power to soft, even as the rest of the world has seemed to go in the opposite direction. President Xi Jinping, for example, has called for “a community of shared destiny,” in which nations are allowed their own development paths while working to increase interconnectedness. (…) It is a new potential soft power proposition: “You don’t have to want to be like us, you don’t have to want what we want; you can participate in a new form of globalization while retaining your own culture, ideology, and institutions.”

Though Eric Li mentions that China has a very broad spectrum of trade and economic partners, it is clear that Latin America has a special role to play in China’s vision for the future. It is not just the roll-call of President Xi Jinping’s many visits to Latin American countries in the 2010s, or the follow-up visits of state dignitaries to China that have continued almost like a revolving door up to the current year. Underpinning these visits are a series of major investments by China in Latin America’s infrastructure: Chinese companies invested around $160bn in Latin America between 2000 and 2020,5 a figure that has increased steadily over recent years.

China’s most important partner in Latin America is Brazil, and this explains the surge of interest in Portuguese in Chinese universities in recent years. And thus we come on to our second poem, “I Don’t Know How Many Souls I Have”, by the Portuguese poet, Fernando Pessoa, translated by 江晨轩 (Jiang Chenxuan):

我不知道我有多少个灵魂 Não sei quantas almas tenho.

每时每刻无不变换 Cada momento mudei.

每时每刻令我陌生 Continuamente me estranho.

既无所见,也无所寻 Nunca me vi nem achei.

众多之中,我只有一个灵魂 De tanto ser, só tenho alma.

那些找到自我的人,不曾拥有安宁 Quem tem alma não tem calma.

所见仅所见 Quem vê é só o que vê,

所想异所想 Quem sente não é quem é,

留意我所见,我又是谁 Atento ao que sou e vejo,

我渐渐变成了别人,而不是我 Torno-me eles e não eu.

我的每一个梦想,每一个期望 Cada meu sonho ou desejo

都是如此产生,并不属于我 É do que nasce e não meu.

我是自己人生路上的风景 Sou minha própria paisagem,

观看着生命的旅程 Assisto à minha passagem,

多彩,变换,孤单 Diverso, móbil e só,

我无法感受身处何处 Não sei sentir-me onde estou.

这就是为什么,我在不知不觉中阅读着 Por isso, alheio, vou lendo

阅读属于我的书页 Como páginas, meu ser

未来的无法预见 O que segue não prevendo,

过往的早已忘却 O que passou a esquecer.

我注意到读过的空白处 Noto à margem do que li

我的所想所评 O que julguei que senti.

再读之后,却道:“这是我吗?” Releio e digo: «Fui eu?»

只有上帝知道,他为我书写这人生之书 Deus sabe, porque o escreveu.

The first thing noted by Jiang Chenxuan, the translator of this poem, was the self-absorbed and obsessive nature of the “eu”, the self focussed on its own identity, what it is like now, what it was like in the past, and concluding with a question that interrogates whether the self even exists. This poem by Pessoa is, of course, a paradigm of the modernist, 20th-century self which is fragmented, heteronymic and “other”. This self that is “diverse, mobile and alone” (stanza 2, line 7), split between what it sees and what it feels, split between the past it was and its elusive present, offers a portrayal of the self that differs enormously from the self we find projected in traditional Chinese poetry – the self of Li Bai, for example in his poem “Quiet, Night Thoughts”:

床前明月光

疑是地上霜

舉頭望明月

低頭思故鄉

(Before my bed lies a pool of moon bright

I could imagine that it’s frost on the ground

I look up and see the bright shining moon

Bowing my head I am thinking of home.)

The “I” of Li Bai’s poem – at least in the English translation – introduces, of course, a personal dimension into the description of the poet looking mournfully up at the moon. Though it should be underlined that the original Chinese poem does not contain the word “I”, that is “我”: the presence of the “I” is surmised based on the customary grammar of Chinese, given the context described in the poem. But, as even the English translation suggests, the “I” of the poem is not the type of self-obsessive “eu” that we find in Pessoa’s poem, as Jiang Chenxuan’s translation makes clear. Indeed, Li Bai’s “I” includes the author of the poem, but it also covers a broader range of individuals, and specifically those who, as a result of their compliance to their social duties, are unable to return home and – as the poem suggests – are unable to lie on their own bed and look out of the window at the moon.

This is where the cultural context comes in. It is in the words, but only if you can see them. Li Bai’s resigned sadness and acceptance that his duty takes precedence over his family is obvious to the Chinese reader, but it is not immediately obvious to the “innocent” European reader. In the same way, Pessoa’s complaint that he doesn’t know how many souls he has, given that his being has been fragmented by his 20th century experience of modernity, will be understandable for the Portuguese reader but not immediately obvious to the “innocent” Chinese reader.

Struggling with the meaning of words in a poem also means struggling with the cultural meanings buried in the “other” culture. Poems are shorthand hieroglyphs of the meaning of culture.

Do these struggles with the hieroglyphs of culture provide insight into the ebb and flow of diplomacy (including cultural diplomacy) and/or hard (including soft) power? China’s engagement with the Spanish-speaking and the Portuguese-speaking countries of Latin America is, after all, the latest in a line of nations who have “interacted” with Latin America in the last 500 years. So are China’s overtures to Latin America just a slightly tweaked version of the military, trade and investment-based colonialism Latin America experienced in the past from Spain, Britain and the United States? Or can it be genuinely seen as a new type of soft power or cultural diplomacy?

One intriguing difference is China’s attitude towards culture and – though it is not mentioned by Eric Li – the palpable difference in China’s attitude towards language. Anglocentrism has arguably been a consistently core ingredient of British and US colonialism,6 but an exclusive focus on Chinese has not been in evidence in China’s recent dealings with Latin American countries. China’s interest in Latin America has, indeed, led to a change in China’s educational system: since 2019 Spanish has been included in the national college entrance exam.7

Learning someone else’s language – as we are discovering this semester – allows you to engage directly with the “deep structure” patterns that underpin that language, ranging from an awareness of the religious customs of the other culture to the notion of selfhood, which is often culture-specific. As a result of translating great poets such as Vallejo and Pessoa into Chinese we have come round to seeing that there are features of the work of a nationally acclaimed poet that allow us to “grasp” something intrinsic about their nation. Poetry is often the best that has been written about the country that it describes, and often – if the writer happens to be a genius, such as Vallejo and Pessoa – the poetry is expected to “represent” that culture to readers from other countries. Famous poems written by famous writers about famous events of a country’s history stay in that country’s memory for longer than many other art forms. Their connection with the specificity of language, with the tonality and musicality of an “accent of the world”, which is, in essence, what a language is, stays with the language that formed it. The poem in turn forms, and even sometimes guards, disciplines and nurtures that language. By not requiring those Latin Americans who will benefit from China’s investment in infrastructure projects in Latin America to learn Chinese, and by investing in the teaching of foreign languages such as Spanish and Portuguese in its own schools and universities, China may have stumbled on one of the keys to a successful programme of co-designed investment in foreign countries. Only time will tell!

[1] Some of the ideas contained in this essay were presented in a lecture given in the Latin American Centre, Oxford University, on 23 October 2018.

[2] The best translation of Vallejo’s poetry is Zhao Zhengjiang’s 2013 Chinese edition of Poemas humanos

[3] The term ‘soft power’ was first used by Joseph S. Nye in 1990; see his book Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power (New York: Basic Books, 1990). The term and the theory underpinning it soon became a common linguistic currency within the discussion of diplomatic relationships and international relations. Nye further refined this concept in Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics (New York: PublicAffairs, 2004). Soft power is here understood to mean the influence which co-opts rather than coerces (i.e. by hard military power) and aims to shape the opinion of others through culture, political values and foreign policies.

[4] https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/08/20/the-rise-and-fall-of-soft-power/

[5] https://www.fdiintelligence.com/content/feature/chinas-growing-footprint-in-latin-america-82014

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anglocentrism

[7]https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202208/03/WS62e9d064a310fd2b29e6ff71.html#:~:text=Some%20middle%20schools%20have%20also,trend%20is%20growing%2C%20she%20added.