BAS Senior Editor Robin Wallis

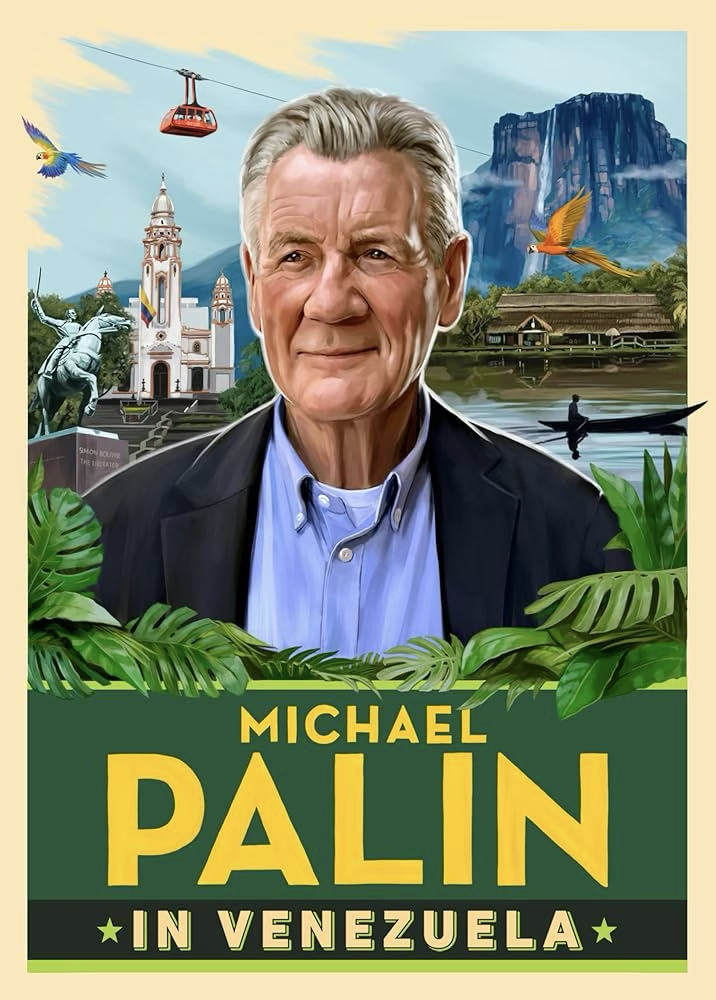

It is February 2025, and Sir Michael Palin and his film crew are in Venezuela to explore one of South America’s best resourced but most troubled nations.

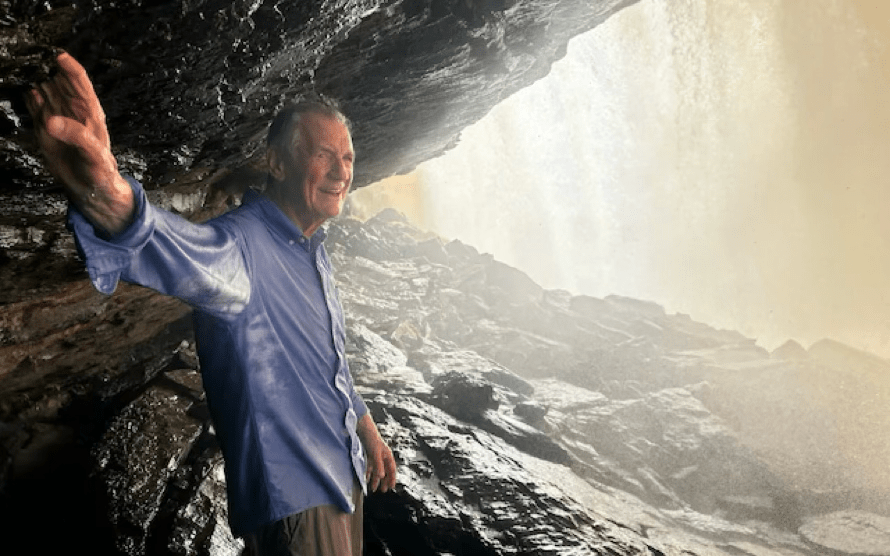

Barefoot on a slippery ledge a few metres behind the thunderous torrent of the Canaima Falls in Venezuela’s Amazon region, the beaming presenter clings to a rocky overhang and hollers to camera, “I’m 81 – I shouldn’t be here!”

“Shouldn’t be” is in effect the mantra of Palin’s Venezuela project – a three-week expedition which has yielded a 3-part television series broadcast in the UK on Channel 51, and the beautifully presented travel journal In Venezuela published by Penguin2.

Having risen to fame as a member of the Monty Python comedy team in the late 1960s, Palin has been a travel documentary presenter on British television since the 1980s. Like Sir David Attenborough in the natural world, Sir Michael’s pedigree as a traveller is such that viewers know to trust his judgement. After 25 years roaming the earth for the BBC, since 2018 he has made a series of shorter documentaries for ITN Productions. The destinations chosen (North Korea, Iraq, Nigeria) have been more challenging than in his earlier days. At an age when most people are looking for familiar certainties, Sir Michael is not shy of asking probing questions about his surroundings and the forces that shape the societies he visits.

A telling moment in the documentary comes when Sir Michael laments on voice-over that Venezuela shouldn’t be such a difficult place to visit or to relax in. At the end of his journal he concludes that Venezuela’s predicament (in 2025) is ‘inexplicable’.

This judgement may reflect Palin’s notoriously benevolent personality. His viewers may be less charitable, shouting back at their television sets that the explanation is obvious: Latin America’s caudillo culture (strong-man rule through violence and intimidation), an elite that has historically prioritised its own interests above the common good, a politicised judicial system that undermines the rule of law, and ‘state capture’ by what Chávez’s opponents called the boligarquía (a pun on Chávez’s fanciful claim to be the political heir to 19th century Venezuelan Liberator Simón Bolívar). Plus the Bolivarian regime’s semi-covert alliances with the masters of repression in states such as Cuba, Iran, Russia and others, where periodic culling of political opponents is standard practice for rulers who wish to stay in power forever.

García Márquez aficionados may find Palin’s ‘inexplicable’ remark reminiscent of Crónica de una muerte anunciada / Chronicle of a death foretold, the García Márquez novel that perhaps reveals more about Latin American culture and society than any other published work. Twenty-seven years after an inexplicable tragedy, the Chronicle’s narrator struggles to ‘reassemble the broken mirror of memory from so many scattered shards3’ and make sense of the event. So too Michael Palin arrives in Venezuela some 27 years after Chávez first won the presidency, trying to understand what has brought about the country’s ruin. Palin muses on what might have been as he wanders through the semi-abandoned oil capital of Maracaibo, and surveys the devastation of Los Llanos’ illegal gold mines – scenes comparable in tone to García Márquez’s narrator hunting for the judge’s report in the flooded public records office in Riohacha4.

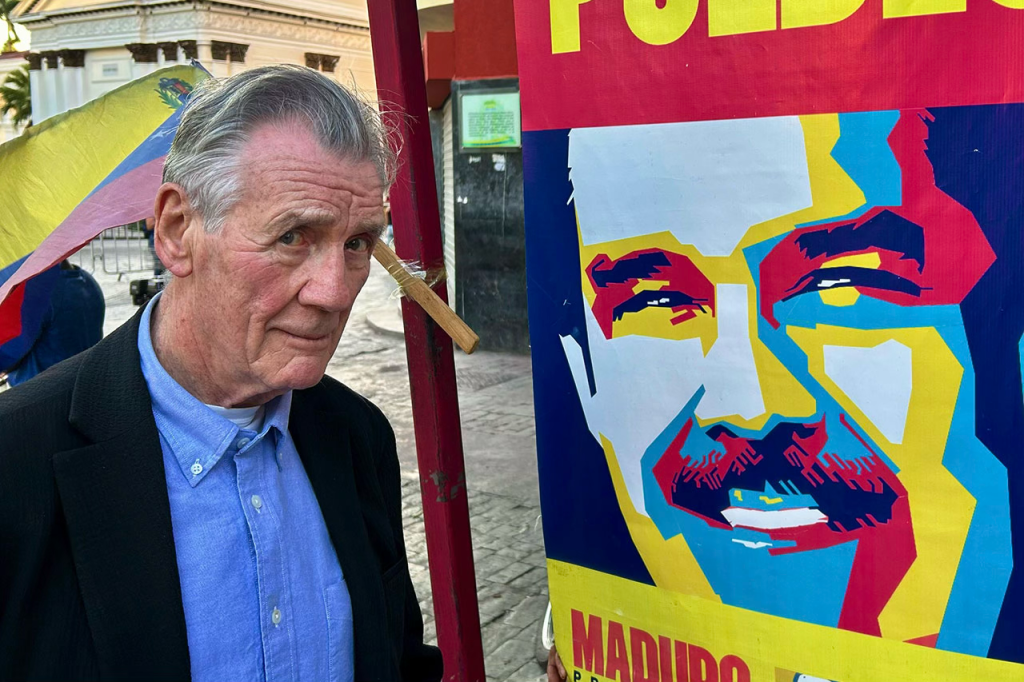

Some Venezuelans speak openly to Sir Michael. Others have to be edited out to protect their identities. All the while the shadow of the police state hangs over the journey – most notably when Palin and his team are informally detained when visiting Chávez’s home town of Sabaneta.

Palin’s comic sensibilities help to remind us that dictators can also be absurd. We chuckle with him at Maduro and his wife portrayed as giant inflatables of the kind typically found outside US car dealerships, or as carnival floats, or in an airline’s in-flight comic depicting the president as Superbigote (to Maduro’s fans, a type of Superman; to Palin, an unintended pun on the term ‘bigot’; and to Spanish speakers, a reminder that Maduro’s moustache (bigote) seems for him to have somehow become part of his entitlement to rule).5 The journal reveals that Palin’s detention in Sabaneta was ended partly as a result of his captors finding on YouTube the fish-slapping dance from Monty Python, performed by Palin and John Cleese – proof that Sir Michael couldn’t be all bad.

Just as visitors to Costa Rica are immersed in the country’s pura vida culture, so one of Sir Michael’s local fixers explains to him that in Venezuela life reflects the dichotomy of tensa calma. From the outset Sir Michael is struck by the uneasy security situation and the regime’s omnipresence. He commendably focuses on what it is like for Venezuelans to live under such despotism, speaking to families divided by exile and young people unable to express their aspirations.

Given Maduro’s fateful encounter with the US Delta Force just under a year after Palin’s visit, you might imagine that In Venezuela has been overtaken by events. Conversely, you could argue that the toppling of Maduro has made Palin’s observations all the more significant as an insight into a society desperate for change, yet one where – owing to the quashing of free elections and other civil rights – people have been unable to express their needs.6

Palin makes a persuasive case that Venezuela will be worth visiting as/when it emerges from dictatorship. He finds unspoiled coastal communities, spectacular scenery and some inspiring affirmations of the human spirit – notably, the Project Alcatraz programme to rehabilitate violent offenders through rugby, run by an altruistic rum distillery owner whose premises had been targeted by criminals.

If you have time for only the documentary or the journal….

The TV visuals vividly convey how hazardous some of the journey was, the sense of threat, the characters of Sir Michael’s interlocutors, his disarming way of ingratiating himself with local people and the telegenic nature of his wit (eg his announcement to camera that the Caribbean beach he was visiting was so idyllic that he had decided to retire from film-making there and then, so the camera crew could all b***er off).

The journal offers some fuller and more nuanced insights than we find in the documentary. The author and publishers have shrewdly assessed the reading public’s appetite for / tolerance of detail about faraway places, and have duly kept the journal to 20,000 words. They have also worked out that a large proportion of their readership is likely to appreciate the easy-on-the-eye font, generous line-spacing and sumptuous photographs. Sir Michael is a champion of the Third Age not just in being able to scramble over slippery rocks in his eighties.

One thing is certain: touring Venezuela without a production company budget to protect you from the privations suffered by regular citizens would be a risky and probably disagreeable experience. Or so it was under Maduro. Now that Venezuela is ‘run by’ the US government, that should change… shouldn’t it?

- https://www.channel5.com/show/michael-palin-in-venezuela ↩︎

- Whether Palin or his distinguished publishers were consciously echoing the title of Bruce Chatwin’s seminal 1977 classic In Patagonia, the two works are quite different genres: illustrated travel journal (Palin) / travel literature (Chatwin). ↩︎

- recomponer con tantas astillas dispersas el espejo roto de la memoria – Crónica chapter 1 ↩︎

- During his Venezuela trip Palin is reading García Márquez’s novel El General en su laberinto, which depicts Bolívar’s withdrawal into exile, driven by disillusionment with the self-interest of local elites in places like Caracas. (Bolívar died before he could board ship.) ↩︎

- cf Fidel Castro’s trademark beard in the Cuban revolution – so potent a symbol that the CIA at one point instigated a (failed) plot to make said beard fall out. ↩︎

- Maduro lost the 2024 presidential election, but lied about the result to claim victory, forcibly oppressing opposition protests. ↩︎