BAS Senior Editor Robin Wallis

A thousand years ago the great cities of Moorish Spain were a confluence of Jewish, Arabic and Christian communities. Historians debate how authentic this convivencia actually was, but it seems clear that for much of the Moorish occupation different communities across the peninsula avoided feuding and respected each other’s traditions. Visit Andalusia today to witness the heights of civic engineering, artistic refinement and architectural elegance they attained, often the fruit of collaboration across the religious divide.

Alas… Iberia was not immune from the human propensity for selfishness and bigotry. Centuries passed and the politics of conquest required that the homeland be ethnically cleansed. There followed forced conversions and expulsions of Jews and Moslems, with all the misery that entailed.

The message of hope is that Spain is now a tolerant multi-ethnic society where Jews, Moslems and Christians can again live side by side. A law passed in 2015 allowed Sephardic Jews descended from those expelled in the 15th Century to claim Spanish citizenship.

The sad news is that some of the descendants of those expelled are, five hundred years later, caught up in yet another bout of blood-letting at the other end of the Mediterranean. Despite the efforts of courageous peace activists on both sides, the rancour that many Israelis and Palestinians feel for each other seems to have become an inherited trait, passed from each generation to the next. A critical mass of men on both sides accept the use of violence… and so it goes on.

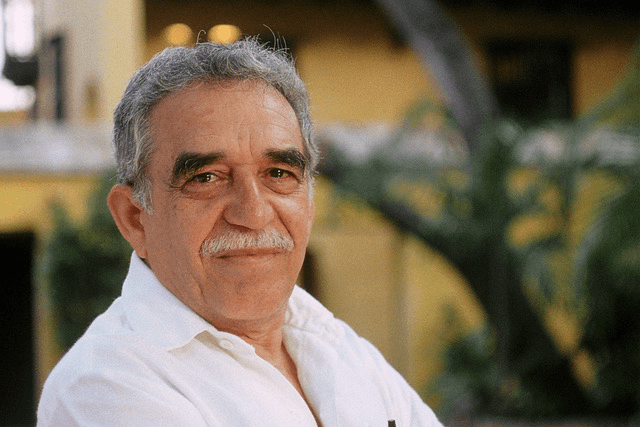

The Israel-Palestine conflict puts me in mind of the conclusion to García Márquez’s great allegory of Latin American history Cien años de soledad (One hundred years of solitude), where the narrator hauntingly affirms that las estirpes condenadas a cien años de soledad no tienen una segunda oportunidad sobre la tierra (‘races condemned to one hundred years of solitude do not have a second opportunity on earth’). In the case of Israel-Palestine, the solitude / separation has lasted much longer than one hundred years. How badly they need their second opportunity.

Another García Márquez classic, Crónica de una muerte anunciada (Chronicle of a death foretold), depicts events in a pueblo olvidado (forgotten town) near the Colombian Caribbean coast. Santiago Nasar is a member of the Middle Eastern community there: he is depicted as prosperous and fully participating in communal life, equally at ease around the bishop or the burdel. Ethnicity is not a barrier to co-operation or participation.

Happily, this kind of unproblematic integration seems to have been the norm for the 5% or so of Latin Americans with Arab ancestry. Eleven presidents of Middle Eastern origin have held office in Latin America, including the current incumbent in El Salvador, Nayeb Bukele, who is of Palestinian descent.

Latin America was a popular destination for Christians from Lebanon and Palestine when the Ottoman Empire collapsed after the First World War. Santiago de Chile is home to the Palestino football club, whose slogan (Desde 1920 representando al pueblo palestino) indicates its enduring ties with its kinsmen living under Israeli occupation.

Unsurprisingly, governments around Latin America are sympathetic to Palestinian statehood. Nonetheless, an Israeli-Palestinian War is uncomfortable for them, given the United States’ commitment to Israel. Venezuela’s close ties to Iran and Cuba further complicate the mix.

I leave the last word to the two Spanish artists whose exposés of the horrors of war are among the most powerful to be found in any gallery.

In the case of Francisco Goya (1746-1828) his repudiation of war reached its zenith in his 82-print series Los desastres de la guerra (1810-20), which depicts the barbarity and suffering brought about by the Peninsula War of 1808-14. For his biographer Evan Connell, the prints represent ‘a prodigious flowering of rage’. The scenes are so graphic that there is not one that we are comfortable with reproducing here.

We turn instead to the two large-canvas masterpieces Goya painted to commemorate the uprising that started Spain’s War of Independence against the occupying French army.

El 2 de mayo de 1808 en Madrid conveys the tragedy of the townspeople, abandoned by the authorities that should be protecting them. They are forced to use makeshift weapons to take on a remorseless French army, fronted by los mamelucos – a regiment of recruits from the Arabic-speaking world, with all the historical associations that entails in the Spanish context.

Its partner piece El 3 de mayo… depicts the execution of captive Madrid patriots in the pre-dawn of the following day. The central figure is a larger than life working-class hero, whose white shirt and outstretched arms convey a sense of defencelessness, injustice, defiance and outrage as he confronts the faceless firing squad.

Together, the two works emphasise the plight of civilians suddenly exposed to the rigours of a ruthless foreign power – a universal theme all too relevant to conflict scenarios in the present day, and which reaches its most forceful expression in Picasso’s anti-war masterpiece Guernica.

Pablo Picasso is celebrated as a master of multiple artistic styles and media, but his single most famous painting commemorates an atrocity from early in the Spanish Civil War. Guernica is a vast (775 x 350cm) canvas painted in response to the merciless aerial bombardment of a Basque village by Nazi aircraft in the service of Franco’s military campaign in late April 1937, killing up to 300 civilians. Picasso’s achievement is all the more spectacular for the speed with which he accomplished it (35 days): it was already on display in early June that year. The work repays prolonged attention as the viewer ponders the various possible interpretations of Picasso’s symbolism and his juxtaposition of universal images of human suffering (eg the bereaved mother) with more specifically Spanish motifs, principally the bull.

Guernica toured the world for many years until finding a home in Madrid’s Reina Sofía Museum, half a mile from the Prado Museum housing Goya’s masterpieces. Since it was painted, Spaniards have learned to value peace and accept compromise. Alas, that journey is not yet completed in all lands.