BAS editor Helen Laurenson

Every morning during her last winter, the old woman walked around the rectangular terrace of her apartment. She moved slowly, pausing at intervals to take in the view. From this high vantage point, or her eyrie as she called it, the city lay spread and luminous in the early summer light. To the east, beyond the Hotel de Inmigrantes and the docks, the river traced its wide brown path towards the sea. She remembered summers at the balneario, young men and women swimming, full of vigour and life, with not a thought for what would come. As night fell, the terrace of the Cervecería Munich would fill up and French lanterns illuminate the smiles of the people as they walked through the glorieta to reach the pier. Now nothing remained of Costanera Sur, it had long since been transformed into an industrial waste ground where no-one ventured. However, it was to the western side of the terrace where the woman’s gaze lingered. To the Plaza del Retiro where the gods had lived. With an imperceptible smile, she turned her back on the view and moved towards the stone apex of the terrace, just as she had designed it, the bow of her ship. The gaucho’s daughter and her Edificio Kavanagh had outlived them all.

Buenos Aires’ architecture earned the city the sobriquet of the ‘Paris of Latin America’, and during the gilded age it seemed that many buildings were endowed with a sense of the monumental. The modernist Edificio Kavanagh is one of many such buildings, whose architects collectively embraced a hybridity of styles and both European and North American influences. From grandiose yet utilitarian water pumping stations such as the ‘Palacio de Aguas Corrientes’ of 1894, to the ‘Catedral de Electricidad’, a power station opened in 1928 and nicknamed Nuestra Señora de la Electricidad by porteños, there was a clear sense of architectural innovation and experimentation.

Indeed, this fiebre de París, bolstered by the new-found prosperity generated by agriculture and livestock, fuelled a building boom summed up in Gaudí’s words No Hi Ha Somnis Impossibles (There Are No Impossible Dreams) emblazoned on a building by Spanish architect Rodríguez Ortega on Avenida Rivadavia. Both foreign and Argentine architectural firms took full advantage of the capital flooding into the country, and of the appetite of wealthy clients to design ever more ostentatious buildings, particularly in the Art Deco and Modernist traditions.

The first quarter of the 20th century also saw the arrival of pivotal Italian architects keen to develop their portfolios outside the restrictive Italian school, in particular Francesco Gianotti (1881-1967) and Mario Palanti (1885-1978), who between them designed some of Buenos Aires’ most emblematic buildings: the Palacio Barolo, the Hotel Castelar [1], El Palacio Chrysler [2], Galería Güemes and the Confitería El Molino. The emergence of eclectic modernism, in parallel with Art Nouveau, Art Deco and Rationalism, explains the construction in the 1930s of such disparate buildings as the American Art Deco style Edificio Kavanagh and the gigantic and exaggerated French style Edificio Estrugamou [3]. The architectural historian Eduardo Lazzari affirms this, stating, ‘una característica de los arquitectos argentinos es la de siempre generar una broma arquitectónica, es decir un detalle que no se corresponde con lo canónico y que le da un toque significativo’.

This fascination with the architectural language of Paris – specifically Beaux-Arts – has its roots in the fin-de-siècle when more mansions per family were built in Buenos Aires than anywhere else in the world [4]. Indeed, the Argentine Centennial of 1910 continued in this vein, with the construction of public buildings and monuments donated by the countries of immigrant communities settled in Argentina.[5] The first two decades of the 20th century saw established patrician families – the Blaquier, Alvear and Anchorena families amongst others – jockeying for position in an increasingly uncertain world, where industrialist nouveau riche interlopers and immigrant Marxist sympathisers from Russia threatened the social and political status quo.

It was into this climate of socio-cultural apartheid that Corina Kavanagh Lynch was born on 20 February 1890, the daughter of Irish immigrants from Ballygarrett, Co. Wexford and County Westmeath. At the age of 22, Corina was married to Guillermo Ham Kenny, the wealthy son of a fellow Irish landowner, Peter Ham of La Choza, Luján, whose obituary states, ‘Mr Ham, through his persevering industry and uprightness, amassed an immense fortune since his arrival in the Plate’.[6] Four years older than Corina’s father, Guillermo lived the typical life of the Argentine elite – con la vaca atada [7]– owning estancias in the Pampa and studs in Chantilly, whilst developing a taste for European high life.

The couple lived outside Argentina for sixteen years, with Corina amassing French antiques, haute couture and jewellery, and clearly fine-tuning her interest in architecture. When he died, Corina became even more wealthy: even so, societal expectations in such a patriarchal society were that she would still require a husband despite her independent wealth. She duly went on to marry Carlos Mainini, her husband’s doctor and a TB specialist whom she met in Paris and married in August 1929 – a marriage annulled by the Vatican six years later. So far, not so good. In 1938 – y para más INRI – she married the patrician bisexual Héctor Gustavo Casares Lynch, whose father was a founding member of the ultra-elite Buenos Aires Jockey Club [8]. None of the marriages were particularly happy, despite her fabulous wealth and lifestyle, and she remained childless, living out her days in apartment 14 of the Edificio Kavanagh until her death in 1984 aged 93.

The urban myth of Corina Kavanagh centres on the construction of the 31-storey, 120-metre-high residential skyscraper in 1936, at the time the tallest building in Latin America and the highest reinforced concrete structure in the world. The building occupies a triangular shaped site in front of the Basilica Santo Sacramento and adjacent to the Plaza Hotel, facing the Plaza San Martín in the Retiro barrio of Buenos Aires.

The building, commissioned by Kavanagh, was designed by the Argentine architects Gregorio Sánchez, Ernesto Lagos and Luis María de la Torre. It is said that Corina Kavanagh had to sell several estancias in Venado Tuerto [9] in the province of Santa Fe to fund the cutting-edge project, which had 105 luxury apartments for rental, with hitherto unseen levels of sophistication as regards fittings, finish and design[10]. Its Impact was immediate: in 1939 the American Institute of Architects ranked it as a technical achievement alongside the Eiffel Tower, Aswan Dam and Panama Canal. In 1999 it was declared a national monument and part of UNESCO’s World Heritage of Modern Architecture.

Theory and speculation swirl around Corina’s motivation for the project. Already in possession of the French-style Palacio Kavanagh in the northern suburb of Olivos, Corina did not hesitate in purchasing the future Edificio’s plot of land when it became available on the Plaza del Retiro. Ownership of this plot allowed her to exact architectural revenge on the self-styled ‘Condesa Pontificia’ Mercedes Castellanos de Anchorena (pictured), who had spurned Corina as nouveau riche. The ultra-pious Condesa had founded the adjacent Basílica del Santísimo Sacramento in 1914: Corina’s carefully designed skyscraper achieved near total occlusion of the view of Basilica Santo Sacramento from the Palacio Anchorena, the Condesa’s family mansion on the other side of the Square. The snub was lost on the Condesa, who died in 1920, 16 years before the Edificio was built, but presumably brought satisfaction to Corina.

With Corina’s second marriage dissolved in Paris, she returned to Argentina. Rumours suggesting an amorous liaison between Corina and the Condesa’s son Aarón de Anchorena, soltero de oro argentino, entertained Argentine socialites of the mid-1930s, but remain unproven. On 17 March 1938 Corina married her third husband, Héctor Gustavo Casares Lynch.

Perhaps the most edifying aspect of the Corina legend is not the alleged vendetta with the Condesa, but rather the revolutionary nature of both the building and its creator. In the midst of the Depression, and in a society where men dominated commerce and real estate, Corina Kavanagh broke boundaries aesthetically and socially. Allegedly inspired by New York’s Rockefeller Building[11], the Edificio Kavanagh was conceived, designed and built in 20 months, a testament to Corina’s tenacity and a very different rate of progress from that of the Rockefeller, which took eleven years of design controversy. Corina’s bold envisioning of this corner of Plaza del Retiro made a clear modernist statement with its perpendicular, avant-garde façade so in contrast with the existing low-level skyline of domes, mansard roofs and belle-époque embellishments. The impact of the building was not merely aesthetic: as the ambitious crie de coeur of a woman excluded yet triumphant, it constituted a subtle destabilisation of the social status quo.

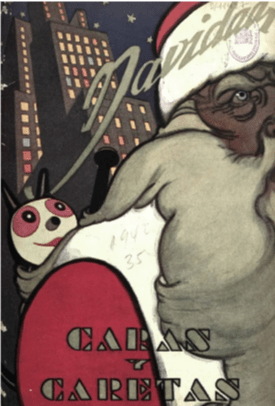

Despite all her wealth, Corina’s story was that of immigrant Argentina, and her building really was ‘La Pampa puesta de pie’ [12]. From featuring on the cover of the society magazine Caras y Caretas’ Christmas edition of 1935 to being voted most iconic building in Buenos Aires by the city’s inhabitants in 2017, there is no doubt that la hija del gaucho se hizo la América.

[1] The hotel on Avenida de Mayo where García Lorca stayed from October 1933 to March 1934 during the premiere of Bodas de Sangre in the Teatro Avenida. The hotel opened in 1929 and was designed by Mario Palanti, who also designed the Palacio Barolo.

[2] Now called Palacio Alcorta, the building comprised a one-mile rooftop automobile test-track and was built in 1928.

[3] This building is an architectural anomaly which imitates Parisian belle époque on an exaggerated, proto-brutalist scale.

[4] See for example, Palacio Paz (1902-1914), now the Círculo Militar; Palacio San Martin (1905-1909) home of the Anchorena family, now the Ministry of Foreign Affairs; Palacio Pereda (1919), now the Brazilian Embassy, el Palacio Ortiz Basualdo (1912), now the French Embassy.

[5] Monuments were exported from France, Italy and Spain, with the British gift of the Torre de los Ingleses placed strategically in front of the Retiro railway station which opened in 1915, whose steel construction was shipped from Liverpool and apocryphally intended for Australia.

[6] https://www.genealogiafamiliar.net/getperson.php?personID=I23467&tree=BVCZ

[7] This curious expression – tener la vaca atada – connoting extreme wealth, finds its origin in the transportation by ocean liner of family, servants, domestic animals and even cows to provide fresh Argentine milk when in Europe.

[8] https://www.diariodecultura.com.ar/costumbres-y-tendencias/la-fascinante-vida-de-cora-kavanagh-la-mujer-que-invento-el-edificio-mas-iconico-de-buenos-aires/

[9] Founded by the Irishman Eduardo Casey and known as ‘La Esmeralda de Sur’ due to the fertile landscape.

[10] Originally conceived as luxury rental apartments, fittings included imported American kitchen appliances, a cold fur store, reception, garden terraces and 12 lifts.

[11] The Rockefeller Building is twice the height.

[12] Prologue, Marcelo Nogué, Kavanagh