BAS editor William Chislett

Which is the only European capital with an Islamic origin? It is Madrid, whose name apparently morphed from the Arabic term mayrit (meaning ‘plenty of waterways’) during the Muslim presence in large swathes of Spain between 711 and 1492.

The city’s cathedral and its Virgin, Our Lady of Almudena, take their names from the walled citadel, the al-mudayna. The cemetery that bears her name is the largest in Europe: at least 5 million people are said to lie, or have lain, under the earth there.

This and many other generally unknown facets of Madrid make Luke Stegemann’s Madrid: A New Biography (Yale University Press) a fascinating and engaging read. The author writes with the detached clarity of an outsider (he is from Brisbane), but the insight of one who has lived for some years in various parts of Spain and still visits regularly.

Not surprisingly, José Luis Martínez-Almeida, the Mayor of Madrid, ever eager to promote the city, invited the author to present the Spanish edition (Madrid: Historia de una ciudad de éxito) at a public event, which he did in July this year.

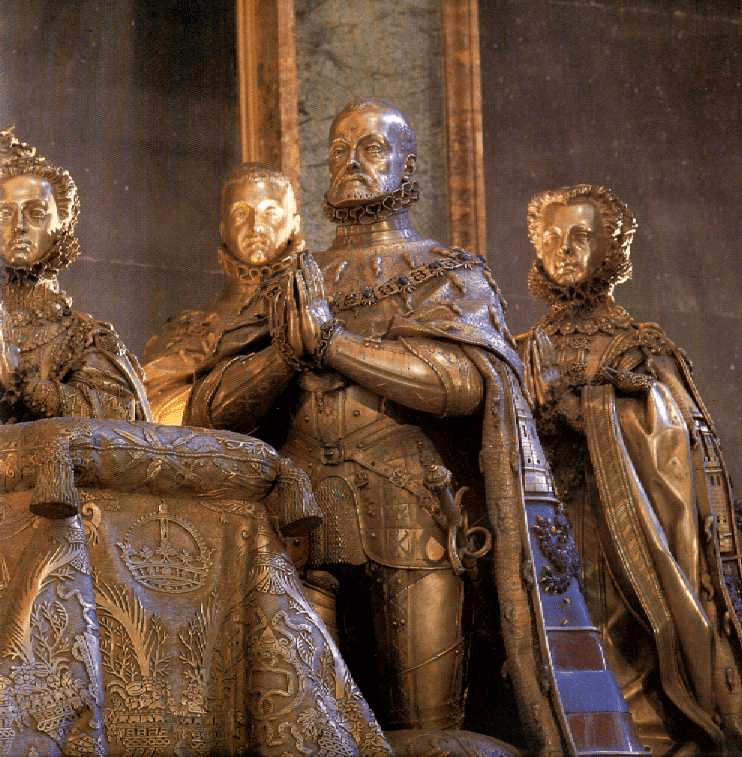

His ‘biography’ of Madrid charts the origins of the city, founded around 865 AD on the site of a Visigoth settlement, and its evolution into Spain’s capital in 1561, when King Felipe II installed the court there, ending the anomaly of having an empire but no capital city. His father Carlos I (Emperor Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire) had moved his court between Toledo, the Archbishopric and long-term seat of ecclesiastical power, and Valladolid.

There is no conclusive evidence that explains the move to Madrid. Felipe himself spent most of his time shut away in the stark monastery that he subsequently built in El Escorial, some 45km from the capital. The common assumption for choosing Madrid was that it is bang in the centre of Spain. Stegemann suggests another reason might have been that ‘the arrival of the modern state meant it could not be beholden to the Church, vital though that institution was’: the royal court needed its distance from Toledo.

Divided into four sections –Village, Iron Age to 1616; Empire, 1516-1759; City, 1759-1975; and World, Into the twenty-first century– this is a richly detailed book. Stegemann draws on all manner of books, paintings and his own experiences. The bibliography takes up 11 pages and there are 564 notes. The book is as much a sweeping history of Spain as it is of one city, and does for Madrid what Robert Hughes, a fellow Australian, did for Barcelona in his 1992 book Barcelona: the Great Enchantress. As a 40-year resident of Madrid, I learned a lot.

Madrid was not part of the Grand Tour, the 17th– to early 19th century custom of travelling through Europe, with Italy as a key destination, mainly undertaken by wealthy young European men. Madrid might not have been given its due because, says Stegemann, it was the capital of a country ‘considered an outlier among the civilised on the basis of modes of behaviour or governance common elsewhere’. In other words, he suggests Madrid was a victim of the so-called ‘Black Legend’, the term used to describe anti-Spanish Protestant propaganda whose roots date back to the 16th century when Roman Catholic Spain’s European rivals sought to demonise the Spanish Empire and its achievements.

Even today more international tourists go to Budapest, Valencia, Barcelona and Istanbul than to Madrid, the EU’s fourth most populous metropolitan city. Thankfully this has saved it, so far, from the overtourism that is angering the residents of Barcelona and other coastal destinations. Madrid attracted only 7 million of the 85.3 million international tourists that visited Spain in 2023.

The city has over 1,800 monuments, 200 historic buildings and 70 museums, including the Prado, Thyssen and Reina Sofía, the three art temples within easy walking distance of one another, but most tourists just want sun, sand and sea.

Medieval Madrid was advanced for its time, with its own fueros, or code of laws, which pre-dated King John of England’s Magna Carta by a decade. These laws applied only to Christians, as Muslim and Jewish communities followed their own laws, although in cases of conflict the fueros took precedence.

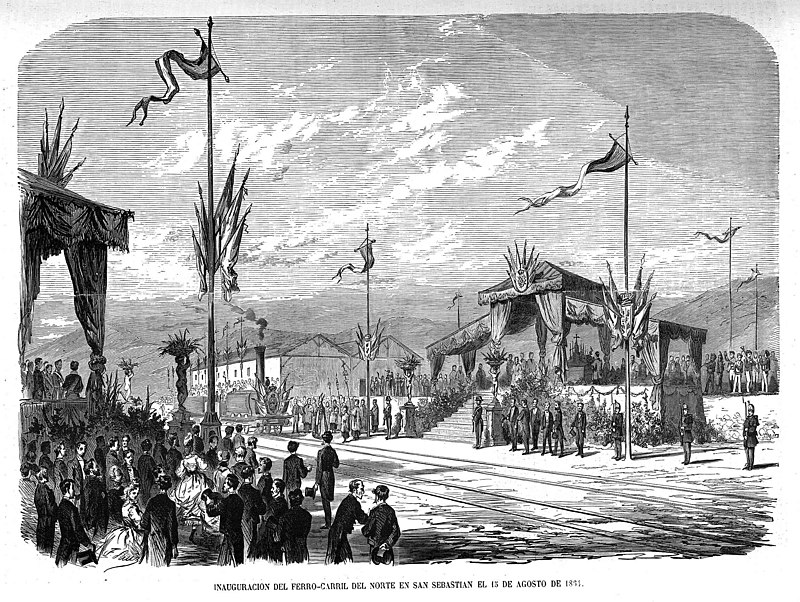

The city expanded in the middle of the 19th century, attracting people from other parts of Spain, aided by the arrival of the train. By 1864, the Madrid-Irún line had been inaugurated, linking the capital with the French border. Between 1852 and 1860, the population increased as much as in the previous 50 years, before hitting half a million by the end of the century, 200,000 more than in the 1860s.

Today, foreigners account for 19% of the city’s population of 3.5 million, many of them Latinos, earning Madrid the epithet ‘European capital of Latin America’. Since 2019 the region of Madrid (population 7 million) has been the main motor of the Spanish economy, overtaking Catalonia, historically the powerhouse.

The city has had more than its fair share of violence, including the entry of the French during the Peninsular War, commemorated in two of Goya’s most famous paintings ‘The Second of May, 1808 and ‘The Third of May, 1808’ hanging in the Prado; the brutal bombarding of the Republican stronghold during the 1936-39 Civil War by Franco’s Nationalists, which forced the government to move to Valencia; and the killing of 193 commuters in 2004 when bombs exploded on trains to Atocha station in Europe’s worst jihadist attack. Madrid also suffered the most killings outside the Basque Country by the terrorist group ETA (123 of the 853), including the assassination of Admiral Carrero Blanco, Franco’s first prime minister, in 1973.

Unlike Spain, whose national anthem has no words, Madrid put words to music for its official anthem, created in 1983. ‘¡…sólo por ser algo, soy madrileño!’ (Just to be something, I’ll be a madrileño’) goes one line. The city is a lot more than ‘something’.

Adapted from the version originally published by the Elcano Royal Institute.