BAS editor Robin Wallis, with contributions from fellow-editor Helen Laurenson

A good tune catches our attention and opens our ears to a song. A good lyric achieves a lasting impact, and makes the song worthy of repeated listening.

My objective here is to identify certain techniques used by the Spanish songwriter Joaquín Sabina to write memorable lyrics. I hope that this will intrigue readers with an interest in the Spanish language, while also raising awareness of the lyricist’s art, an arguably under-explored sub-genre of literature. It is also perhaps fitting to mark the year of Sabina’s 75th birthday with an hommage to his distinctive style, as represented in the songs Noches de Boda, La canción más hermosa del mundo and Ruido – ending with a reminder of his lighter side.[1]

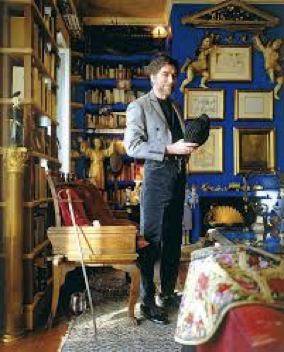

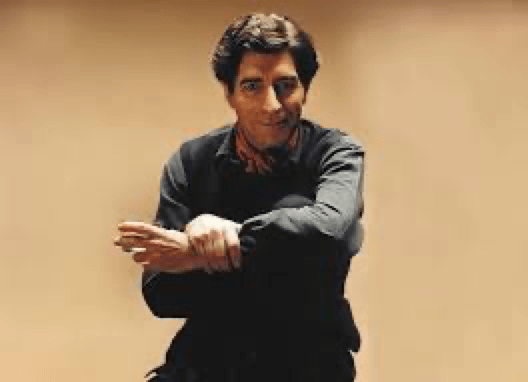

Growing up in Andalusia in the 1950s and 60s, Sabina absorbed the musical genres of the Spanish-speaking world while also immersing himself in rock and folk, not least during his exile in London (1970-77). His career as a singer-songwriter thrived on his shrewd selection of songwriting partners to expand his musical repertoire. He also mastered the art of being a personaje mediático (thinking person’s celebrity) with a refreshing disdain for proprieties, without ever coming across as inauthentic or crude.

Sabina wrote poetry from an early age. His study of Spanish-language verse enabled him to compose lyrics that included inspired re-working of both Golden Age and 20th century canonical poetry. Pablo Neruda and César Vallejo[2] were a formative influence on him. His admiration for Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen is apparent in his repertoire.[3]

Noches de boda (1999) typifies the way in which Sabina can build a song lyric around a simple refrain, not to embed a catchy musical hook in the listener’s ear, but rather to emphasise particular linguistic phrases for poetic effect. In this case, the repeated ‘Que + subjunctive’ invites listeners to join with the singer in what amounts to a secular prayer, gently and wistfully expressed in a celebration of conjugal love and resistance to the ravages of time. The repeated que structure builds up momentum behind the expressions of hope, heightening the audience’s empathy with the singer. Listeners no longer have to adjust to each successive phrase: they focus instead on each new image or association, which becomes all the more personal to them within a wider, universal framework. The juxtaposition of the mundane with the poetic/surreal generates a synergy between day to day reality and higher aspirations – what Helen Laurenson has called the hibridez sabiniana[4]:

Que el maquillaje no apague tu risa

Que el equipaje no lastre tus alas

Que el calendario no venga con prisas

Que el diccionario detenga las balas

Que el corazón no se pase de moda

Que los otoños te doren la piel

Que cada noche sea noche de bodas

Que no se ponga la luna de miel

La canción más hermosa del mundo (2002) also plays with language structure to evocative effect, blending Sabina’s immersion in popular culture with the lyrical and syntactical tropes of the Golden Age – a hybrid fusion of lo popular y lo culto.

It opens with a commonplace phrase of everyday language – Yo tenía (‘I had’, or perhaps, ‘I used to have’). He follows this with a lengthy incantation of nouns, the next verb not surfacing until line 12 (and that in a subordinate clause):

Yo tenía un botón sin ojal, un gusano de seda

Medio par de zapatos de clown y un alma en almoneda

Una hispano olivetti con caries, un tren con retraso

Un carné del Atleti, una cara de culo de vaso

Un colegio de pago, un compás, una mesa camilla

Una nuez, o bocado de Adán, menos una costilla

Una bici diabética, un cúmulo, un cirro, una estrato

Un camello del rey Baltazar, una gata sin gato

Mi Annie Hall, mi Gioconda, mi Wendy, las damas primero

Mi Cantinflas, mi Bola de Nieve, mis tres Mosqueteros

Mi Tintín, mi yo-yo, mi azulete, mi siete de copas

El zaguán donde te desnudé sin quitarte la ropa

The accretion of disconnected nouns might at first sight appear random or nonsensical. However, as the images mount up, it becomes apparent that they depict a cycle of possession and loss charted through cultural markers and nostalgic associations. The juxtaposition of the mundane, the personal, the abstract and the transcendent throws the opening tenía into melancholy relief, and sets up the climactic declaration of loss:

No sabía que la primavera duraba un segundo

Yo quería escribir la canción más hermosa del mundo

Yo quería escribir la canción…

The cantautor has had to face up to his limitations, but has no regrets. His failure is redeemed by the stoicism and dignity with which he acknowledges what he has lost or not achieved. The irony is that, in doing so, he has after all managed to escribir la canción.

Ruido (1994) tells the story of a doomed relationship. The first half of the lyric features some of Sabina’s most poetic language, set to flowing rhythms, eg:

Ella le pidió que la llevara al fin del mundo

Él puso a su nombre todas las olas del mar…

Todas las ciudades eran pocas a sus ojos

Ella quiso barcos y él no supo qué pescar

Despite being so absorbed with each other, the couple’s incompatibility undoes them. The melody contracts to a more staccato rhythm for the ten stanzas that track the relationship breakdown. Disorientated by the ruido (noise) generated – figuratively or literally – by the overwhelming weight of nouns, the couple stand no chance:

Ruido de tenazas,

Ruido de estaciones,

Ruido de amenazas,

Ruido de escorpiones.

Tanto, tanto ruido.

Ruido de abogados,

Ruido compartido,

Ruido envenenado,

Demasiado ruido.

The clamour oppresses them. There is no escape. The bleak but convincing conclusion is…

Tanto ruido y al final

La soledad.

In focusing on language structures, I have hitherto chosen examples with wistful and melancholic themes. Yet humour and comic irony are central to Sabina’s work and public persona. As a corrective, I would recommend Pacto entre caballeros (1987) and Pastillas para no soñar (1992) – humorous and ironic takes on surviving the urban jungle, playfully depicting life on the edge. The mucha, mucha refrain on which Pacto…. closes illustrates how a song allows its writer to subvert normal language to comic effect.

Sabina’s sense of humour is perhaps most famously showcased in his satire on Spanish machismo, 19 días y 500 noches (1999), with an extract from which I shall close:

Tenían razón mis amantes

en eso de que antes el malo era yo,

Con una excepción:

Esta vez yo quería quererla querer

Y ella no.

Así que se fue,

me dejó el corazón

en los huesos

y yo de rodillas.

Desde el taxi,

y, haciendo un exceso,

me tiró dos besos…

uno por mejilla.

For a definitive overview of Sabina’s place in and impact on Spanish culture, see https://bulletinofadvancedspanish.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/bas-5.3-june-2022-archive.pdf: Joaquín Sabina: ‘Ni juglar del asfalto, ni el Dylan español’, by Helen Laurenson.

Footnotes:

[1] A number of websites carry the full lyrics to these pieces, some with parallel versions in English – though such translations are usually unintelligible and smothered in advertising. Even the few where some effort has been put into the English version serve mainly to illustrate how hard it is to translate song lyrics. They do at least help English speakers to work out the meaning of unfamiliar vocabulary without recourse to a dictionary or Google Translate.

[2] El Comercio 28/05/2015:

“Sabina se refirió al arte de crear mundos a través de los versos, tal y como lo hicieron dos grandes de la poesía: el peruano César Vallejo y el chileno Pablo Neruda.

Aunque confesó ser un admirador de los dos, aseguró que si lo obligan a elegir solo a uno, preferiría al autor de “Los heraldos negros” (1918), cuyos poemas se sabe “enteritos de memoria”.

Sobre uno de los grandes intérpretes de la música a nivel mundial, Bob Dylan, dijo que es ‘un fuera de serie’ al cual escucha todavía, con el mismo interés que le despertó la primera vez, cuando apenas tenía 17 años.”

[3] The interface of singer-songwriter with the literary structures and lexis of canonical literature can also be found in the work of Bob Dylan and Dylan Thomas, for example, or Lewis Carroll and John Lennon.

[4] https://bulletinofadvancedspanish.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/bas-5.3-june-2022-archive.pdf: Joaquín Sabina: ‘Ni juglar del asfalto, ni el Dylan español’