BAS editor Nathanial Gardner

Not too long ago a friend of mine came back from Germany and asked me with a hint of exasperation, but also with genuine interest: “What is going on with Frida Kahlo? Why are so many people interested in her?”

There had been a minor exhibition of Frida’s work in the German city that my friend had visited, and the queue to see it had been over two hours long. My friend had been pressed for time, so hadn’t been able to see what so many others were willing to stand in line for.

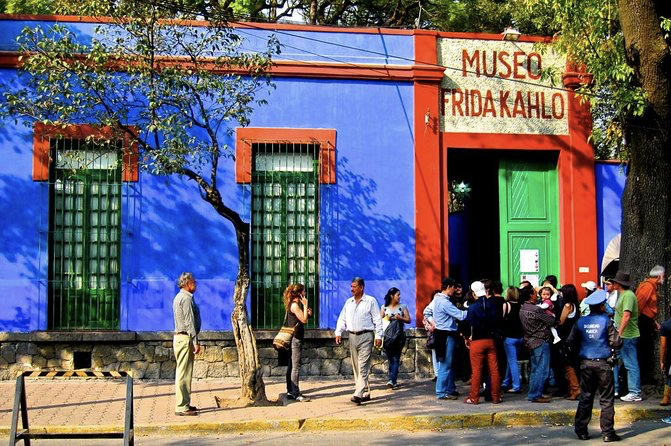

I too have been a first-hand witness to the huge growth in interest in absolutely anything Frida-related. Only a little over ten years ago, anyone could walk up to the Frida Kahlo Museum in the leafy and quiet Mexico City suburb of Coyoacán and buy a ticket that cost roughly £1 to see her home and her art. Never once did I wait in line to get in (and if you were a student or a teacher they would even let you in for free). Once inside, the venue was quiet and you could easily have a room to yourself to contemplate for a while.

Today, everything has changed. Gone are the days when you could simply walk up and buy a ticket. Now you have to purchase them online many days (and sometimes weeks) in advance. The average ticket will set you back around £30 (US$36) if you are visiting from afar (admission is cheaper if you are a Mexican, a teacher, or a student). Cameras require permits. Carefully coordinated queues of people slowly make their way in at their allotted time. There is a constant murmur of visitors around you, carrying you through the museum on the steady rhythm of their tide.

Frida is big business. In Mexico she is omnipresent. You can find her on t-shirts, bags, posters, trinkets and magnets. You name it, and some aspect of her likeness is probably part of it. Frida is becoming integrally associated with Mexico, and even in some ways with Latin America. But why?

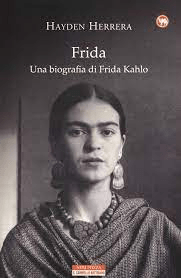

The answer is not straightforward. Some will point to Hayden Herrera’s 1983 biography of Frida Kahlo as a watershed moment. This publication (which started out as her PhD thesis in Art History) came at just the right time. Many of Kahlo’s family and associates were still alive and could be interviewed as part of the project. This meant that her book has personal insights from those close to the artist that help shape an intimate portrait of her. It is a moving and inspiring story that has surely contributed to the increased excitement around the artist.

This book also appeared at a time when some high-profile buyers in the Global North acquired some of Kahlo’s paintings. Some conspiratorially-minded people think that the Frida hype is to help increase the value of those investments. And curiously, the number of ‘lost’ Frida pieces that have recently been ‘found’ makes some suspect that art forgers are hard at work trying to cash in on the heightened profile of the artist.

Whatever the case may be, it is obvious that Frida arouses interest. People like her art and her persona. But why Frida? What did she do?

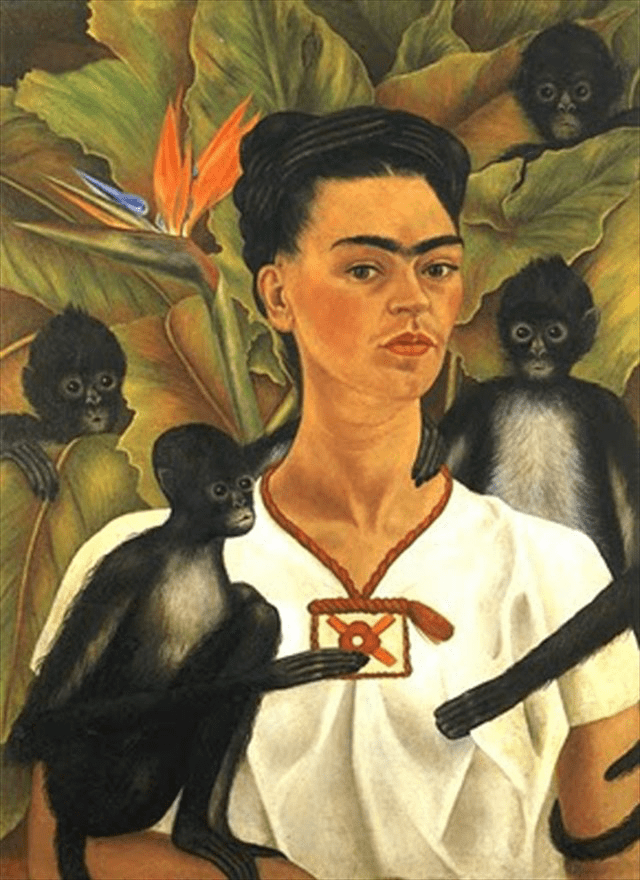

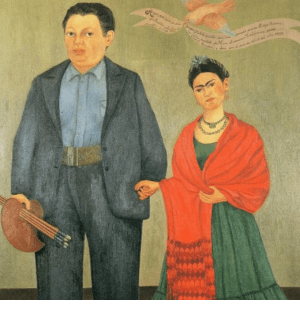

In her day, Frida was firstly known as the wife of Diego Rivera, and secondly as an artist. At that time her muralist husband Diego was possibly her biggest fan, and a huge promoter of her art (though that didn’t stop him promoting himself over everything else). Diego Rivera was also a womaniser, and the suffering this caused Kahlo is evident in her work. Yet this may not have been her greatest cause of pain.

Frida lived in a body afflicted by polio and a devastating tram accident in her youth that affected her every day of her life. She suffered great pain in her spine and had multiple miscarriages, as well as dozens of operations. Towards the end of her life, she lost her foot and part of her leg to gangrene. Hence she was admirable, but not necessarily envied. Yet, who does not identify with some aspect of suffering in their own life?

Perhaps one of the biggest reasons why Frida is so popular is that she is a figure from the past whose life touches aspects of our present and has qualities of modern-day influencers. She was an international traveller. She was friends with the wealthy and the powerful. She spoke more than one language. She loved animals. She had a tormented relationship with someone who adored her, yet who also treated her terribly. She was afflicted with pain in both body and spirit. Yet she found solace in creativity, and her talent was (and continues to be) recognised by many critics and admirers. Perhaps it’s because at least one aspect of her varied and fruitful life is relatable to those who know her work that she is so popular.

Even so, I am increasingly convinced that we are now reaching a point where Frida is becoming like Che Guevara – a Latin American icon who is universally recognised and ubiquitous, but about whom relatively few people are well informed. Having reached that state of ‘Frida saturation’, stardom hollow in substance is definitely a possibility.

How to avoid this? We can begin by learning more about her. Herrera’s book is a great starting point, with excellent references and solid scholarship. Be wary of texts written about Kahlo by those who have very little knowledge about who she is or what she did (there are more of these than you might imagine). Study her paintings. Do this either online or in person if you have the possibility to travel to Mexico. Kahlo does have a body of work worth contemplating, and the Museum in Coyoacán remains the best place to see it. Just be sure to book your ticket in advance.

Where will Fridamania go? I’m not sure, though it is likely that over time the current level of popularity may diminish at least somewhat. In the meantime, one way of thinking of this phenomenon is that, in some small way, Fridamania is a kind of revindication. There was a time when Kahlo would have been known as the wife of Diego Rivera. Now the tables have turned. For someone who loved himself and his own art over everything else, to know his wife’s fame has surpassed his own can be seen as a type of cosmic vengeance.