BAS editor Sander Berg

It is January, the first lesson back after Christmas. At the start of the lesson a finger

shoots up. ‘Sir, when are we going to talk about paedophilia?’

Before the Christmas holidays I had asked my Year 13 to read closely the last two

chapters of Del amor y otros demonios by Gabriel García Márquez. They had all

ostensibly read the novel in English over the summer, so in theory this should have

been a second reading, in Spanish this time. Ostensibly. In theory.

I had mentioned the problematic relationship between Delaura and Sierva María

before and I had given them a ‘trigger warning’, but it was not until they (some of

them at least) had studied the text in detail that they cottoned on to the fact that

Delaura is a 36-year old priest who falls in love (lust) with the 12-year old Sierva

María. Yes, he is three times her age and she is barely pubescent. Cringeworthy

doesn’t come close. Two of the girls in the class described how they found reading it

more uncomfortable (even) than some scenes in Almodóvar’s Talk to Her. Given the

discomfort, it is legitimate to raise the question whether we should read such novels

with our students. Short answer: yes.

We live in interesting times. Not as in the purported Chinese curse — “May you live in interesting times” — would have it, but perhaps not entirely unlike it either. In the past five years or so, secondary school students have, like their contemporaries at university, become much more agitated and assertive.

More questioning and critical, but also less tolerant – ironically – and more sensitive, more easily outraged. Questions around race and gender in particular are real tinderboxes and potentially toxic. To a large extent this critical engagement is to be welcomed as long as it reflects a serious desire to question things and everyone involved is sincerely open to dialogue.

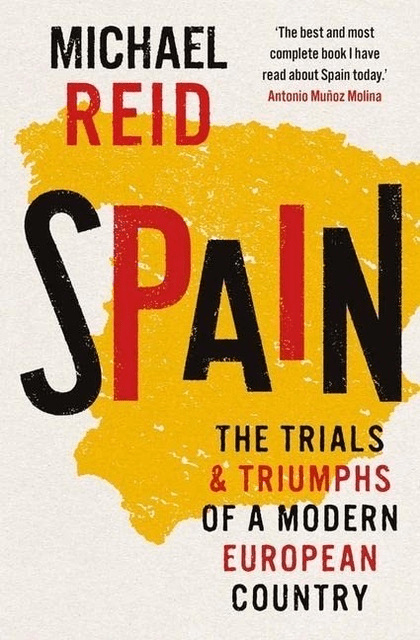

To understand what is happening in the awkward scenes in Márquez’s novel we

need to take two steps back. For Márquez, writing in Colombia in the second half of

the 20th century, a grown man falling in lust with a teenage girl would have been less toe-curling than it is for us. Even today the legal age of consent in Colombia is only 14.

A further step back takes us to the late 18th century and the Spanish colonial

elite, where the age difference might have been even less of a problem. Still, even

with those provisos, there is no need to assume that Márquez is condoning

Delaura’s obsession with Sierva María, much less excusing it, let alone promoting

paedophilia. Delaura’s falling in lust works on a few narrative levels.

On a personal level, he blames his sudden onrush of amorous feelings on the devil; it is a demonic force that takes hold of him. Initially, he does not believe that Sierva María is possessed by the devil and wants to save her. Perhaps he suffers from saviour syndrome. But when he suddenly feels sexually aroused, he convinces himself that it is the work of the devil. Etymologically, this makes sense: Sierva is possessed by the devil (the devil has taken ownership of her) and the devil in her attacks Delaura and besieges him (the origin of the word ‘obsession’).

In fact, quite a few of our terms related to (falling in) love are taken from demonology.

We say we are bewitched, bothered and bewildered, or that someone has put a spell

on us, or encourage someone to go do that voodoo that you do so well. We also

speak of someone’s charms, say we are enchanted when we meet someone

attractive and speak of being fascinated, originally a reference to the evil eye.

Delaura, then, takes literally what we have come to see as a commonplace

metaphor. As the title of the novel has it, love is just another demon.

On a more thematic level Delaura’s obsession with Sierva María works, too. The

novel is steeped in images of decay and decadence. It paints a picture of the dying

days of the Spanish empire, with a wheezing bishop, a nymphomaniac marquesa, a

feckless marqués putrefying away in his hammock, and crumbling buildings on every

street corner. Delaura’s moral turpitude can be read as a symbol of the corrosion and

corruption of Empire and Church.

It is also possible that Márquez, hardly a friend of the Catholic Church, by describing a priest’s obsession with a pubescent girl, might be referring to the institution’s moral

bankruptcy due to its many sex scandals.

Mark Twain once reportedly quipped that the rumours about his death had been

greatly exaggerated. The same is true about the assumption that Delaura has sex

with Sierva María. Sure, there is hanky-panky, and kisses and cuddles, and lots of poetry reading, but Delaura vows to remain a virgin until the day he can elope with

Sierva María and marry her. This hardly improves matters, of course, although I find

it interesting that the same students who first glossed over the age difference on a

second reading make the false assumption that the two have sex. They went from

not seeing the egregious nature of the relationship to seeing things that aren’t there.

A further complication is that Sierva María, after much-spirited resistance, seems to

accept Delaura. Maybe it is because, apart from a short spell with her father just

before she enters the convent, he is the first white person to pay any attention to her.

Maybe she is under the spell of Garcilaso’s love poetry. Perhaps she sees him as a

kind of older brother or a surrogate father. Or perhaps she suffers from Stockholm

syndrome. Who knows?

These are all nuanced questions, but then again, in the world as in good literature,

things are always more nuanced, never black and white. And that is why we need to

read novels like Del amor y otros demonios with our students. What better lesson in

the value of close reading and asking challenging questions and coming up with

nuanced and sometimes uncomfortable answers? What better way to get into a

different, even alien, mindset? We must also guide them and teach them how to

channel their immediate reactions, make them go beyond their initial discomfort and

cringe to take a step back and ask: what is this scene doing here? What does it

mean? What are some of its potential explanations and interpretations? But equally:

to what extent is the scene problematic? What prejudices does it show? What does

that tell us about the time and place in which the novel was set or written? If we cannot read works that challenge us and offer us a vision of the world or a description of events that we find difficult to digest, what, one should ask, are we left with?

In these fractious times, these challenging times, it behoves us teachers to continue to read and discuss ‘difficult’ texts. These can be Canonical, but there are plenty of

other works out there that are worth reading, and it is important to hear different

voices and learn about a wide variety of experiences. Except that we should not expect these works to be plain sailing, unproblematic and in complete agreement with what we already think and believe. We should leave our echo chambers and bubbles and zones of comfort sometimes and venture out into the wide and wonderful world called literature.