James Archer

The backdrop

One hundred years ago Argentina was in the top 10 of wealthiest countries in the world by GDP per capita. In those days Buenos Aires was known as the ‘Paris of the South’. Families leaving Europe would choose between the United States and Argentina in their search for a better life.

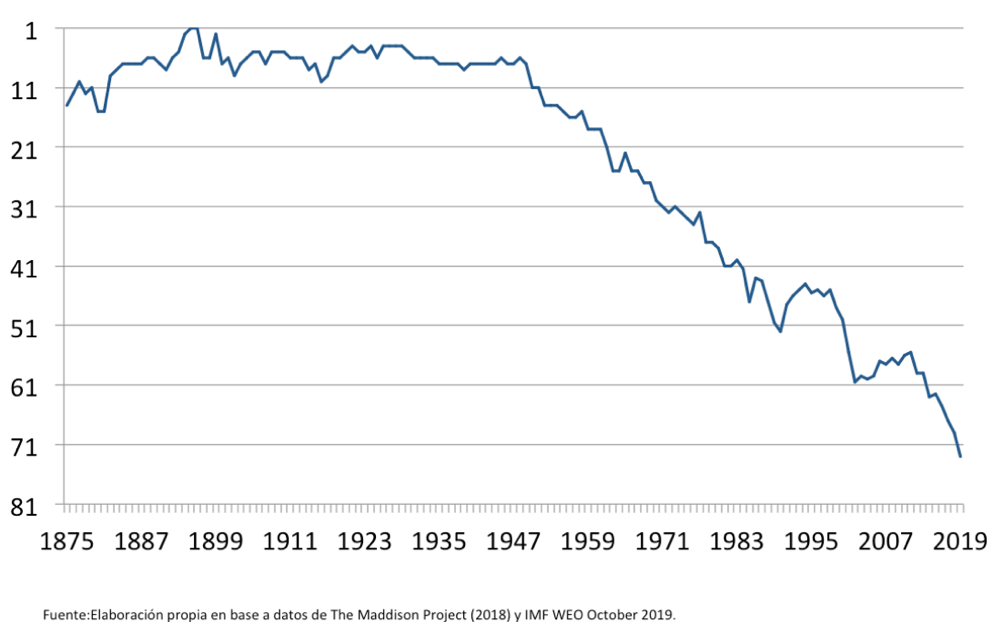

Throughout the 20th century Argentina became a case study of economic decline (see chart), leading to the dictum attributed to US economist Simon Kuznets: ‘There are four kinds of nations: developed countries, developing countries, Japan and Argentina.’

Argentina’s global ranking of GDP per capita

Decades of economic mismanagement, uncertainty and instability have led to tough living conditions for Argentines today. At the time of the presidential election in November 2023, c.44% of the population lived below the poverty line, including approximately 50% of all children. Families struggle to have enough food in a country with the capacity to feed ten times its population of 45 million. The middle class, many of whom have European passports, high levels of education and even higher ambitions, have found opportunities hard to come by. Many seek jobs abroad, resulting in a so-called ‘brain drain’ and cycle of decline.

The election

When Argentines went to vote in November 2023, their choice was between the incumbent government’s finance minister Sergio Massa or the eccentric and erratic political outsider, Javier Milei. As one commentator described it at the time, ‘we are choosing between more of the same misery or a leap into the unknown’.

Sergio Massa had been finance minister of the Peronist-led government from August 2022 to November 2023, an appointment which the then president, Alberto Fernández, hoped would provide political stability. The inflation and peso devaluation for Massa’s 15 months as finance minister were:

| Period | Last 12 month’s inflation | Value of peso, $1 buys* |

| August 2022 | 70% | 300 |

| November 2023 | 140% | 1,000 |

*peso valuation based on the ‘blue’, free-market rate rather than the government-controlled rate.

Supporters of the incumbent government argued that the country had suffered from a severe drought in the summer of 2023, which adversely affected the country’s agricultural export earnings. Critics were quick to point out that Massa had passed a number of short-term laws as he sought to win over voters, including removing income tax for the majority of the population in September 2023 – a move which increased disposable income and added fuel to the inflationary fire.

Conversely, Javier Milei could legitimately claim to be a political outsider and man of the people. He only became a congressman in 2021 and promptly auctioned off his monthly salary in a lottery, which at one point was said to have over 2 million applicants. However, few would deny that Javier Milei has said some unsavoury things, suggesting human organs could be bought and sold and climate change was not a concern.

‘It’s the economy, stupid.’

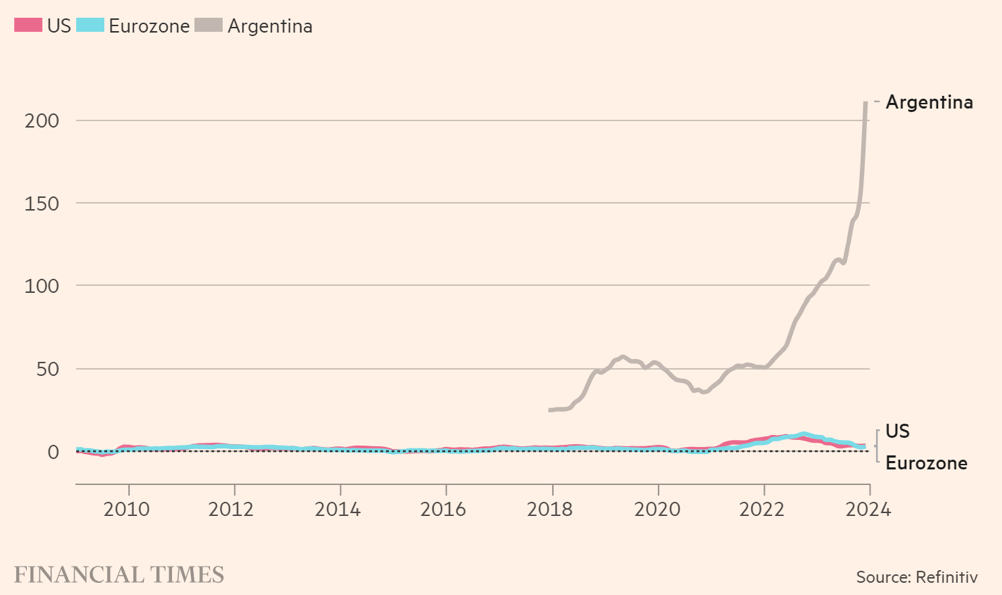

As Argentines headed to the polls, their number-one concern was the economy. Inflation has been a chronic problem in Argentina. People are tired of having their pesos erode in value on a weekly basis, tired of worrying how they could pay for life’s essentials, and tired of a plethora of stories of political corruption (eg just weeks before the election, an official of the ruling Peronist party was found to be cruising the Mediterranean on a hired yacht whilst his party’s supporters could barely afford food).

Worse than high inflation is high, unexpected inflation. With high but predictable inflation one can plan accordingly, knowing how much one’s money will be worth in one month’s time. High unexpected inflation removes that safety mechanism.

Note: Argentina’s inflation metrics pre 2016 were not recognised by independent bodies due to unreliable official figures, with critics accusing the government of manipulating statistics.

As well as being #1 in the world at football, Argentina recently became the ‘leading’ country for inflation. Why so? Most economists point to the significant fiscal deficit and uncontrolled increase in the money supply. The Argentine Central Bank is not independent from the government, so, put simply, prints money to fund government expenditure.

Milei, a self-described anarcho-capitalist, has made reducing inflation and stabilising the economy his key objective. He aims to do so by slashing government spending and running a fiscal surplus.

Many have talked up the likeness between Milei and Trump, and there are similar characteristics, not least the ability to connect with those tired and frustrated with the ruling political elite. Just as Donald Trump riled up crowds with rally cries of ‘drain the swamp’, Milei consistently berated the political caste, urging que se vayan todos (get rid of them all).

Victory and next steps

Milei defied expectations in beating Sergio Massa by 10% (55% to 45%), and was quick to announce he was receiving the worst inheritance of any Argentine government. Milei warned that the coming months would be hard, with inflation likely to increase in the short term and the government’s immediate objective being to prevent hyperinflation.

Since his victory many Argentines are wondering whether Milei will be able to push through the radical changes he proposes. With no majority in either Congress or the Senate, he is relying on political allegiances which to date have not been his strength. His first couple of months in office have seen his far-reaching package of reforms watered down in an effort to reach agreement with minority parties.

Over the course of his mandate Milei aims to transform the Argentine economy by privatising a number of state-run companies, closing down the Central Bank, slashing state spending, removing import and export restrictions, reforming labour laws and, most significantly, adopting the US dollar as the national currency. With opponents mobilising in Congress and on the streets, the jury’s out on whether he will be able to implement even half of his proposals.

The country of Messi, Maradona, and Pope Francis longs to reverse the continued decline of the last 70 years. Only time will tell if Javier Milei is able finally to set Argentina on the right path.

James Archer is a financial analyst formerly based in Buenos Aires.